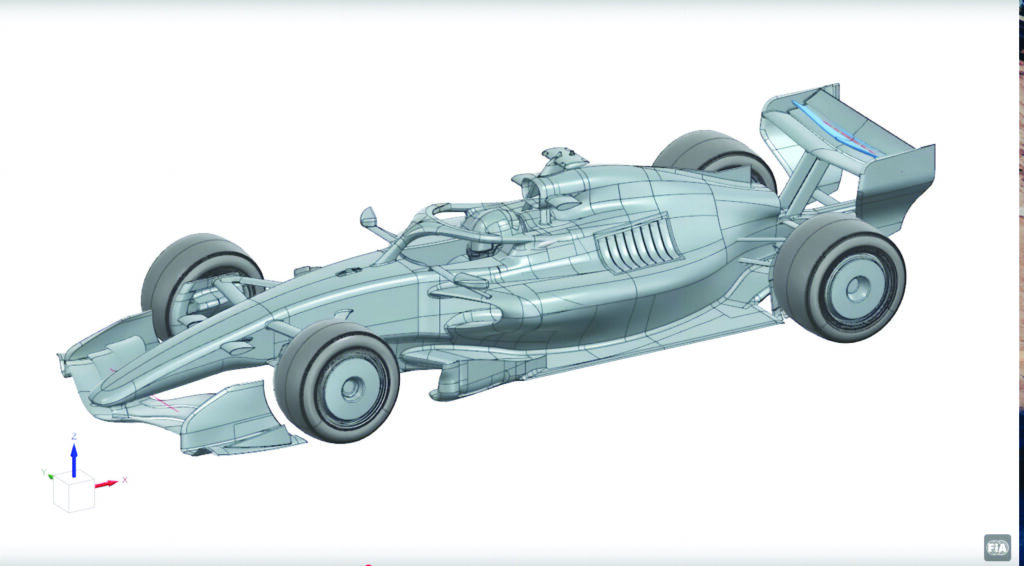

F1 is undergoing its biggest regulation shift this century – or possibly ever. The sport has seen significant changes in the past, including the aerodynamic rules dictating the current cars, and the huge technological jump of the 2014 powertrain regulations. However, in both those cases, it was either chassis or power unit that was altered, whereas 2026 will see wholesale change across chassis, power unit, tires and aerodynamics.

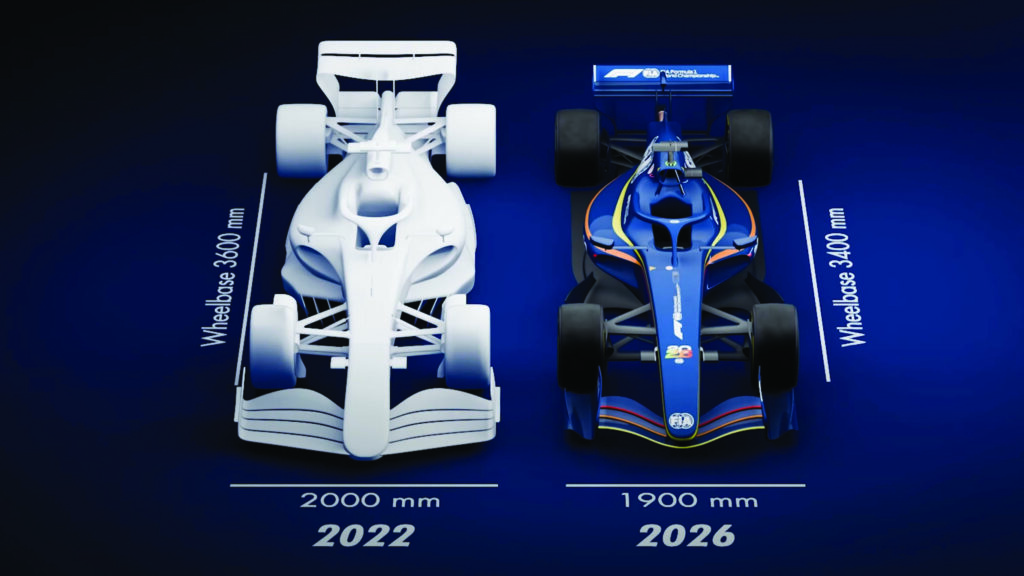

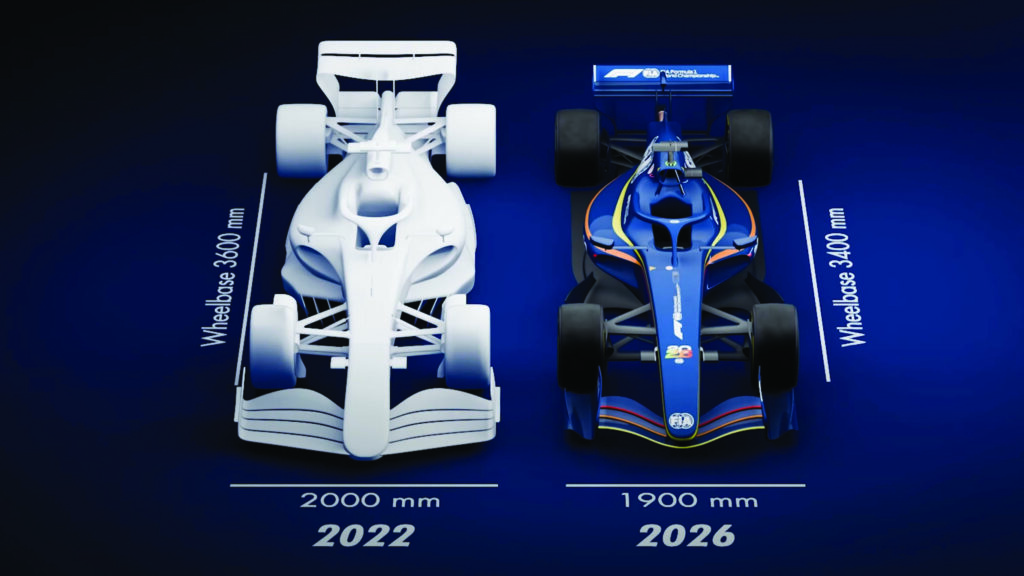

The key aims of the new rules are to enable closer racing and, to a degree, keep costs – particularly for the power unit – in check. The new rules will see cars get smaller, with the wheelbase reduced from 3,600mm to 3,400mm, and the track down from 2,000mm to 1,900mm; tire sizes are also reduced, while the minimum weight will fall from the current 800kg to 768kg.

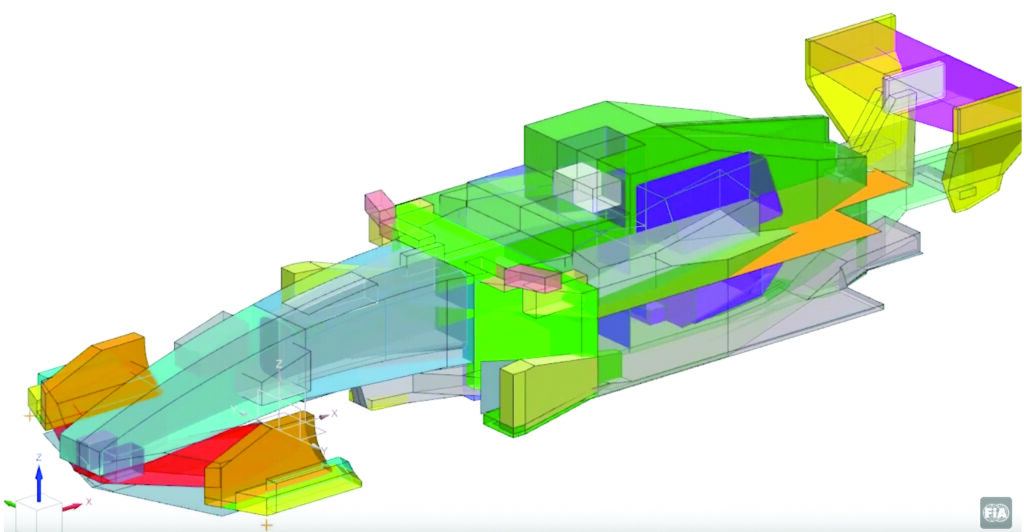

The aerodynamics are also set for an overhaul, with the technical regulations defined to try to harness the gains made with the 2022 regulations regarding wake management. They also aim to eliminate the behavior that led to issues with ‘porpoising’ due to the sensitivity of the underfloor tunnels to variations in ride height. This means that tunnels are out, with a return to flat floors and diffusers.

Significantly, rear and now front wings will feature moveable elements, to reduce drag and account for the very different nature of power delivery from the revised ICE and hybrid systems. Though the basic architecture of the ICE remains, thermal energy recovery is no more. The MGU-H is banned, fuel flow limits have been replaced by an energy use formula, and the power of the MGU-K will be upped from the current 120kW to 350kW. In this feature, we will endeavor to understand the impact of these changes and how various teams across the grid are approaching the new era.

Significantly, rear and now front wings will feature moveable elements, to reduce drag and account for the very different nature of power delivery from the revised ICE and hybrid systems. Though the basic architecture of the ICE remains, thermal energy recovery is no more. The MGU-H is banned, fuel flow limits have been replaced by an energy use formula, and the power of the MGU-K will be upped from the current 120kW to 350kW. In this feature, we will endeavor to understand the impact of these changes and how various teams across the grid are approaching the new era.

2026 F1 Car by Car

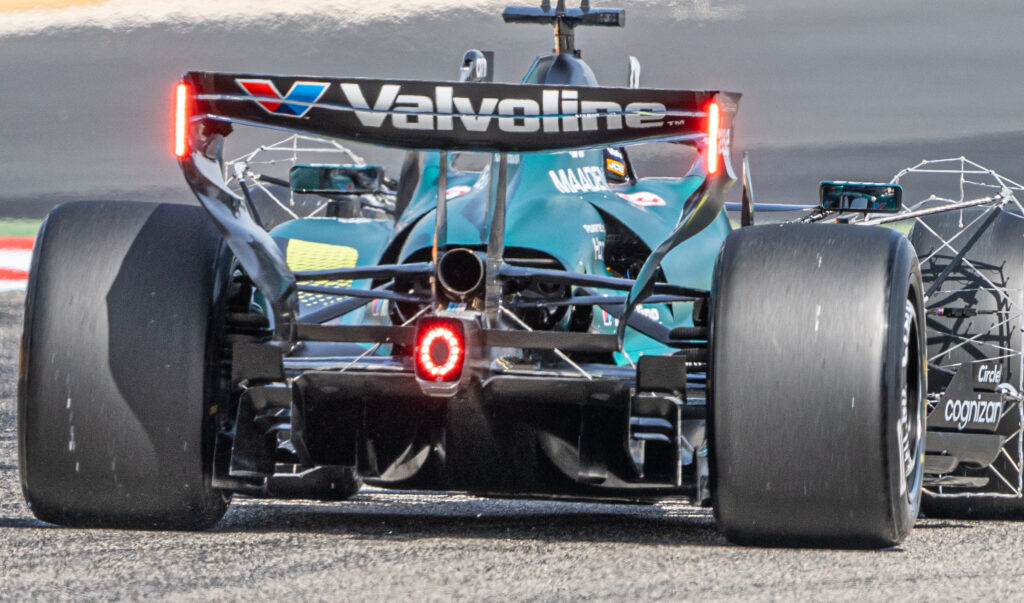

Aston Martin takes on Honda power for 2026, while the AMR26 is the first of its F1 cars to be truly influenced by the pen of Adrian Newey. When the car rolled out in Barcelona, it was immediately clear the team had taken a relatively extreme interpretation of the aerodynamic regulations.

Aston Martin takes on Honda power for 2026, while the AMR26 is the first of its F1 cars to be truly influenced by the pen of Adrian Newey. When the car rolled out in Barcelona, it was immediately clear the team had taken a relatively extreme interpretation of the aerodynamic regulations.

According to Newey, “We took a really close look at the regulations and what we believe we want to achieve from a flow field perspective to suit them, and from there started to evolve a geometry that attempts to create the flow fields that we want. It’s very much a holistic approach……but, in truth, with a completely new set of regulations, nobody is ever sure what the right philosophy is.” Newey also note that, “Yes. The car is tightly packaged. Much more tightly packaged than I believe has been attempted at Aston Martin Aramco before.” However, when compared to some of the other cars in the field, it appears, to the casual observer at least, relatively bulky.

Newey also note that, “Yes. The car is tightly packaged. Much more tightly packaged than I believe has been attempted at Aston Martin Aramco before.” However, when compared to some of the other cars in the field, it appears, to the casual observer at least, relatively bulky.

With the development of its new Silverstone Technology Campus, Aston now has wind-tunnel capabilities in-house for the first time, having previously used both the Mercedes wind tunnel and lately, the TMG facility in Cologne.

“The AMR Technology Campus is still evolving, the CoreWeave Wind Tunnel wasn’t on song until April, and I only joined the team last March, so we’ve started from behind, in truth. It’s been a very compressed timescale and an extremely busy 10 months,” says Newey.

“The reality is that we didn’t get a model of the ’26 car into the wind tunnel until mid-April, whereas most, if not all of our rivals would have had a model in the wind tunnel from the moment the 2026 aero testing ban ended at the beginning of January last year. That put us on the back foot by about four months, which has meant a very, very compressed research and design cycle. The car only came together at the last minute, which is why we were fighting to make it to the Barcelona Shakedown.”

According to Newey, the intent with the car has been to build a car with development potential, rather than one optimized for a tight performance window from the outset. “We’ve tried to do the opposite, which is why we’ve really focused on the fundamentals, put our effort into those, knowing that some of the appendages – wings, bodywork, things that can be changed in season – will hopefully have development potential.”

For Davide Paganelli, head of aero at Haas, the VF-26’s performance isn’t tied to a single element. Instead, it is a game of management. “It’s the management of the floor of the car from a coherent point of view,” Paganelli explains, “starting from the front wing through suspension and the bodywork in order to be able to feed as much as possible with good high-energy flow the rear”.

For Davide Paganelli, head of aero at Haas, the VF-26’s performance isn’t tied to a single element. Instead, it is a game of management. “It’s the management of the floor of the car from a coherent point of view,” Paganelli explains, “starting from the front wing through suspension and the bodywork in order to be able to feed as much as possible with good high-energy flow the rear”.

He notes that the front wing remains the primary tool for setting the car’s aerodynamic behaviour. Teams are currently split on their approach: whether to load the wing more toward the center or the outboard side to manage the wake of the front wheels. With the rules written so as to force in-washing of the wake, the goal of every team is to try and minimise the damage this cause to flow further down the car. Like in the pre-ground effect era, the goal is to retain as much high energy airflow towards the rear of the car as possible, helping to drive the diffuser.

The 2026 Power Units (PUs) have introduced a significant shift in thermal architecture, with a much greater emphasis on the electrical component. While one might assume this requires a radical cooling overhaul, Paganelli views it as a familiar challenge of scale. “The challenge is the same… you try to maximize your heat rejection keeping the volume and the weight as small as possible,” he notes.

The real divergence on the grid is seen in radiator packaging and the shaping of the sidepod inlets. However, the true complexity, says Paganelli, lies in the brake ducts. With high energy recovery from the electrical system, teams must precisely simulate energy management to correctly size the ducts within the tight geometric constraints of the wheel rims, as the design of the external ducts is tightly controlled.

Perhaps the most discussed feature of the new regulations is the move toward active aerodynamics on both the front and rear wings. For Haas, the hurdle isn’t just the mechanism, but the car’s balance in “straight-line mode.” “The main challenge is… to have a car that is drivable also in straight-line mode because the amount of loads that we lose activating both the wings is huge”.

This shift will likely change how teams approach wing levels across a season. Paganelli predicts that the days of bringing six different rear wing specifications to suit various tracks may be over, as the straight-line mode allows for a broader operating window for a single design.

Despite the early-season variety—such as some teams opting for a “high rake” philosophy reminiscent of the period up until 2022—Paganelli expects the grid to converge quickly. Unlike the hidden complexities of the under-floor, the bodywork and wing activation devices of the cars are visible to all. “It’s not like in the floor, that was a sort of hidden area difficult to be observed [driving the performance].”

However, the rapid pace of development is tempered by the budget cap and ATR (Aerodynamic Testing Restrictions). For Haas, the limitation isn’t just wind tunnel hours, but the capacity to run multiple projects in parallel. Having invested heavily in the late-season package for the VF-25, the team is now focused on the iterative refinement of a car where every square centimeter of carbon fiber must earn its keep.

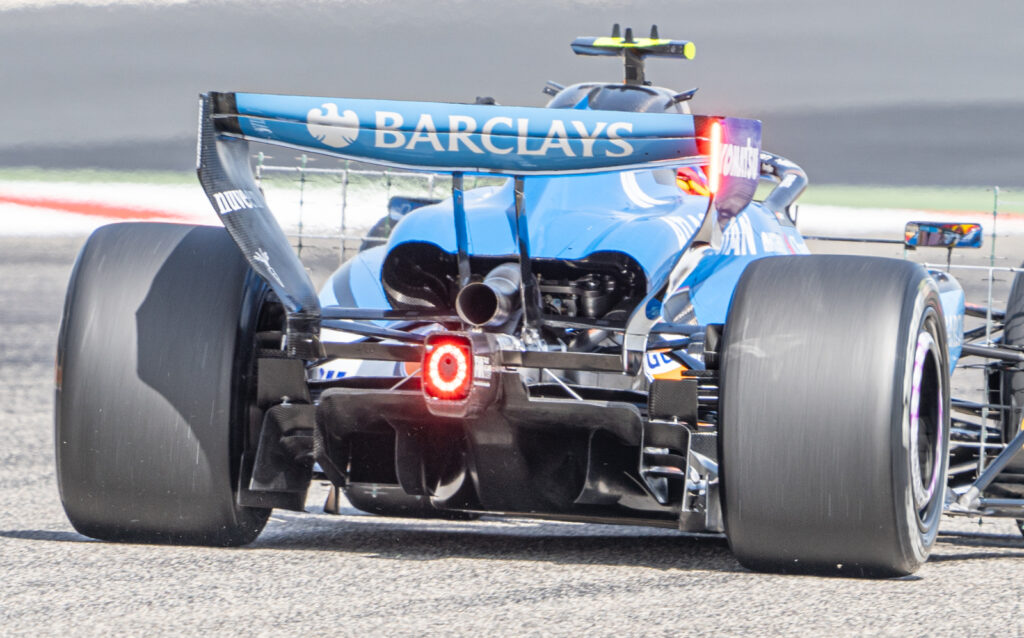

Williams had a hesitant start to 2026, missing the pre-season shakedown in Barcelona, while rumours swirled of an overweight car and missed crash tests. As it turns out, these were just that, rumour, and talking on the first day of pre-season testing proper in Bahrain, team principal James Vowels was upbeat about the the teams progress. Despite missing the initial shakedown, he says, “in lieu of that, we did a full week of VTT (Virtual Track Testing) running where we did quite a few hundred kilometers there. It’s not exactly the same thing as running on track, but you do shake out the gremlins. Followed by two filming days: one at Silverstone and one here [Bahrain] yesterday. The car ran flawlessly yesterday—it was brilliant.”

While Vowels wouldn’t be drawn on the exact weight of the car, understandably, he did not appear to think the team was any better or worse off than others. “I don’t think we’re on the weight limit right now as I talk to you. But there’s a plan in place both for Melbourne and then across the first three rounds or so just to make sure we’re jumping into that. Again, it goes back to: anyone that tells you exactly where they are is probably because they’re right on the weight limit or just below now. But there are sensor packs on the car that are worth around about 12 kilos here just to give you an idea, which is why until you shake that all off, no one knows exactly where [they are].”

Power Units

Details coming soon.

Details coming soon

Details coming soon

Details coming soon

Details coming soon

Details coming soon

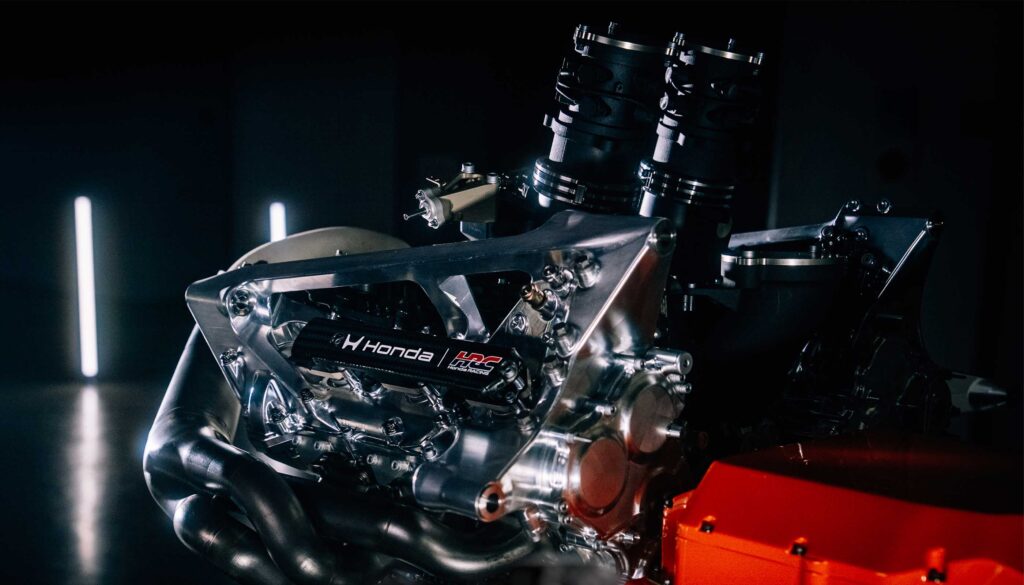

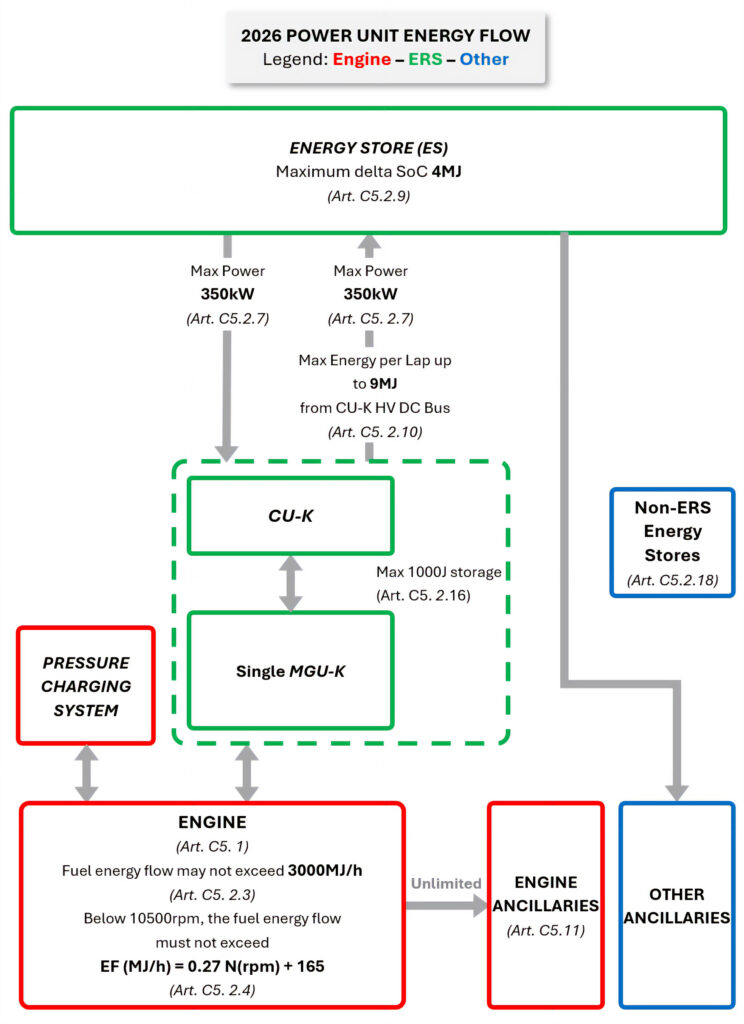

On paper, the changes to the energy recovery systems for 2026 simplify matters, moving from having two energy recovery sources (MGU-K and H) to a single MGU-K. However, the potency of the system more than doubles, from 120kW to 350kW. In theory, with both ICE and MGU on full song, the 2026 cars will be just as, if not more, powerful than the current machines. However, they will only be able to deploy this full power for a relatively small portion of a lap due to limitations imposed by the rules, energy recovery available under braking and harvesting via the ICE at part throttle.

On most tracks, the energy use limit will be set by regulation at 8.5MJ per lap (with the maximum SoC difference in the battery being 4MJ). However, at tracks where the FIA deems it harder to recover energy, the rules (currently) say that this allowance can be reduced all the way down to 5MJ, the intention being to mitigate any vast differences between teams who get a handle on energy deployment faster than the competition. At the time of writing, the rules surrounding where full power from the MGU-K can be deployed were still TBC, though it seems that maximum output will only be allowed as a push-to-pass function and during qualifying.

Furthermore, to prevent a ‘cliff-edge’ scenario of long straights, whereby battery energy is exhausted long before the braking point, available power from the battery will be tapered off at high speed, starting at 300km/h with 0kW available over 345km/h. Away from the energy management issues, which will no doubt consume gigaflops of teams’ computing power during simulation, the mechanical practicalities of the new systems are equally onerous.

As Aston Martin’s Andy Cowell notes, “350kW electric motors do exist in the world, it’s just whether you can get them down to a very lightweight, efficient 350kW. And the same with the battery: there are batteries that take 350kW but again, it’s the mass, it’s the volume and it’s the efficiency.” Starting with the mass of the MGU-K, this is set at 16-20kg, depending on whether the transmission delivering drive to the crank is incorporated within the ERS or the ICE. For reference, the current MGU-Ks have a minimum mass of 7kg. As Mercedes’ Hywel Thomas notes, “Of course, all of us will be aiming at the minimum mass. How close everyone gets, I think, will be an interesting topic.”

The regulations will also fix the location of the MGU-K, placing it at the front of the engine inside the safety cell (currently all teams mount theirs on the side of the engine). According to Thomas, the idea of fixing the location of the MGU-K was “to try to avoid one person coming up with an absolutely stunning idea of where to put it, which then everyone has to copy, and just spending their time copying it rather than actually developing good technology”.

Similarly, the control electronics will also be housed in the safety cell, meaning that there should be no high-voltage cable runs outside of the central chassis, thus improving crash safety. As with the current regulations, the efficiency of the electrical components of the power unit will be just as important as the ICE, the goal being to deploy as much of the permitted electrical power to the wheels as possible. Here the onus will be on the motor and power electronics engineers, and there will likely be some very useful (outside of racing) advances made in the field of high-power semiconductors and motor design, all while respecting the various competing demands of overall car performance, such as reducing cooling requirements to a minimum to keep the aerodynamicists happy

The dawn of the 2026 F1 season will also see the advent of new manufacturer representation on the grid. Audi will arrive with an in-house-developed powertrain and chassis, having taken over Sauber; General Motors will become the 21 st team on the grid with its Cadillac brand; and Ford will come to the fore as the technical partner of Red Bull and Red Bull Powertrains. Although the first two have been keeping to tightly controlled schedules regarding the information they release to the media, Ford has been quite forthcoming about the nature of its involvement in the Red Bull project. Speaking to PMW at the Italian Grand Prix in August, Mark Rushbrook, global director at the newly minted Ford Racing (formerly known as Ford Performance), highlighted that the company’s activities had expanded beyond what it initially expected. “Back three years ago now, when we struck the initial deal, we had a short list of areas where we knew we could contribute and where we also wanted to learn. Initially that was focused more around the electrification, the battery itself: the cell chemistry, the battery pack, the motor and the software around it. That list has grown to much more involvement with the total powertrain and, more than I’d expected, the manufacturing of parts for it. “Where we didn’t expect so much [involvement] is on the ICE. We’re learning there more than we expected, to be honest. But then it’s the manufacturing of the parts. We have advanced manufacturing facilities, we’ve got clients that build hundreds of thousands of units a year, and we’ve got plants that do low volume with additive manufacturing, and that’s where we’re drilling from. Our facilities need to be able to support that, and the number of parts that we’re able to supply – making them in Dearborn and shipping them into Milton Keynes for assembly into the powertrains.” Ford was also able to provide vital capabilities to Red Bull Powertrains early in the development program, helping to reduce development timescales. For example, Red Bull didn’t have in-house rigs for turbocharger testing, which Ford Racing was able to access within the wider company.