When the 2022 WRC season kicked off in Monte Carlo, it marked the start of an all-new era for rallying, and a departure from its conceptual roots. No longer are the cars in the top class, Rally1, based on production chassis. Instead, they are silhouette racers with space-frame chassis clad in all-composite bodywork, built to the rough dimensions of their roadgoing brethren. The new season also saw the arrival of hybrids in the sport, with all three works manufacturers (Toyota, Hyundai and M-Sport Ford) using a spec hybrid unit developed by German firm Compact Dynamics. This move was coupled with a switch to a 100% sustainable biofuel, again standard across the field, supplied by P1 Fuels. It is the largest shift in regulations that rallying has ever seen, driven by a desire to lower the cost, increase safety and more closely align with manufacturers’ marketing aims. PMW spoke to each of the works teams’ technical directors throughout the season to find out more.

Strength and marketability

Two main elements informed the development of the Rally1 chassis regulations: a desire to give manufacturers flexibility to run a wider variety of body styles and incorporating safety features that would be impractical to implement on a production car base. For example, the switch to a space-frame chassis enables the crew to be located more centrally in the car, with greater room for side impact protection. The fully fabricated chassis also means the hybrid system can be housed at the center of the car, protected within the confines of the safety cage.

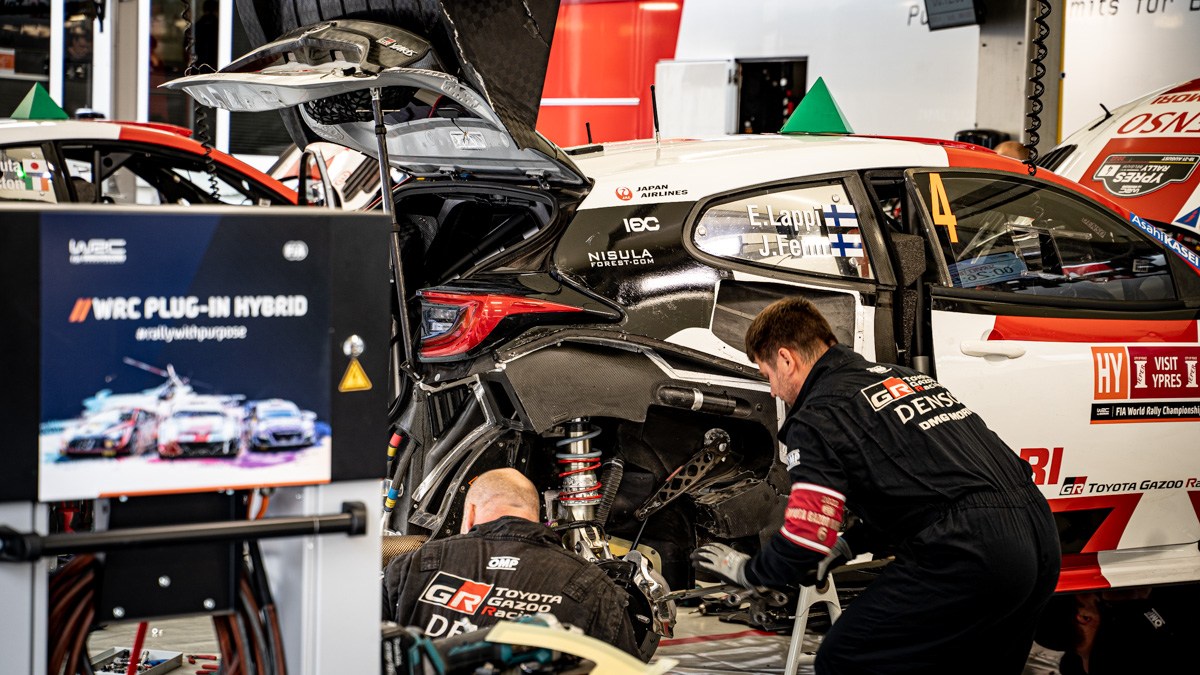

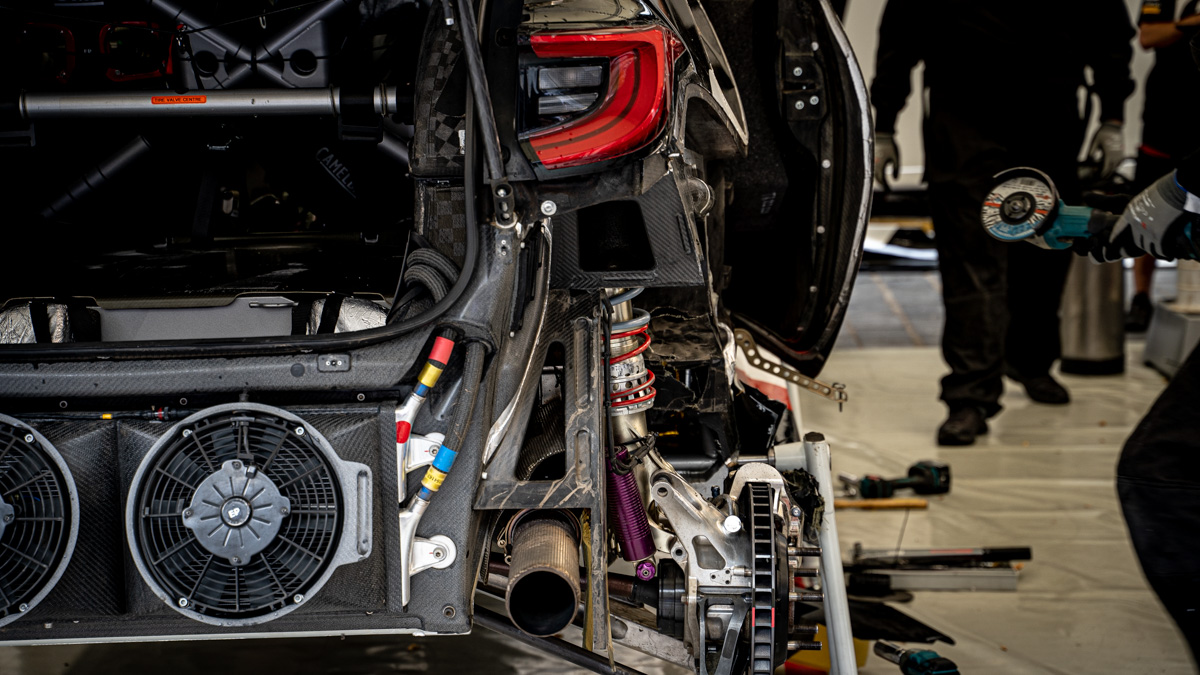

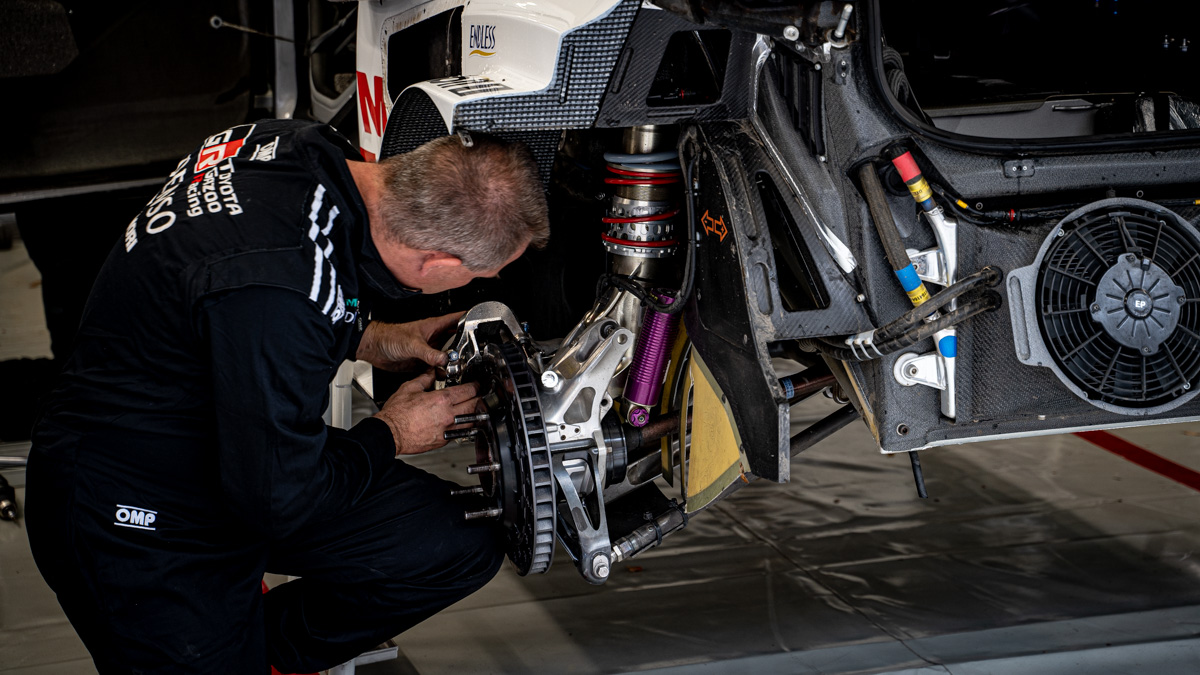

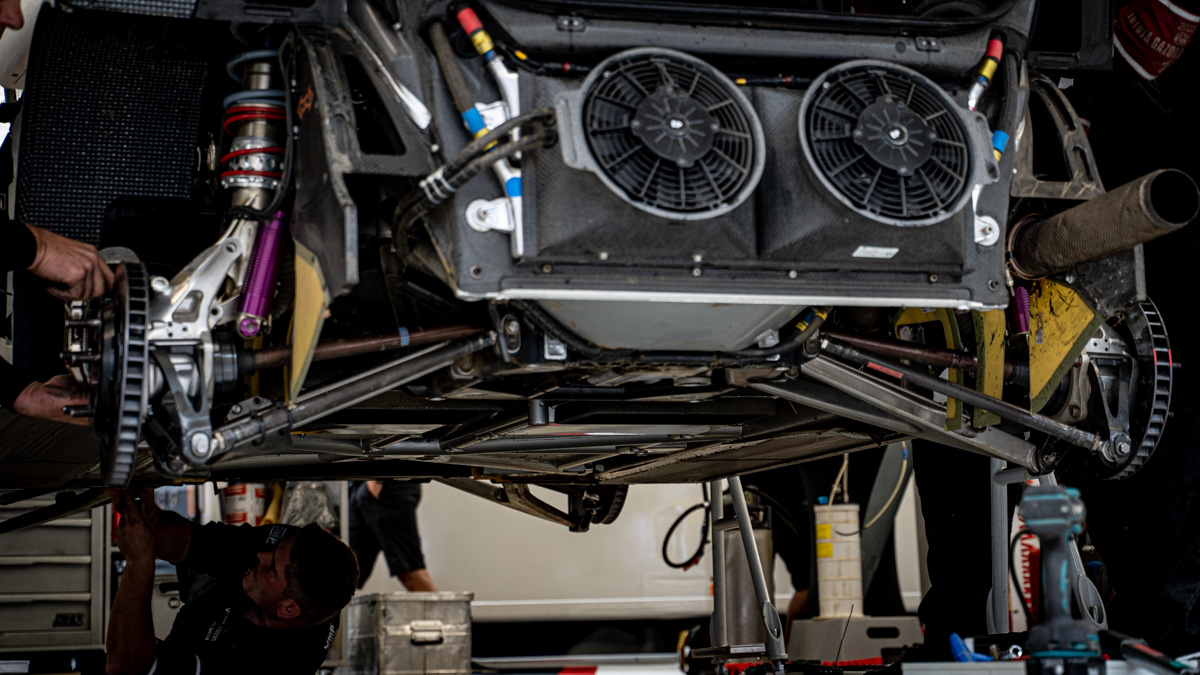

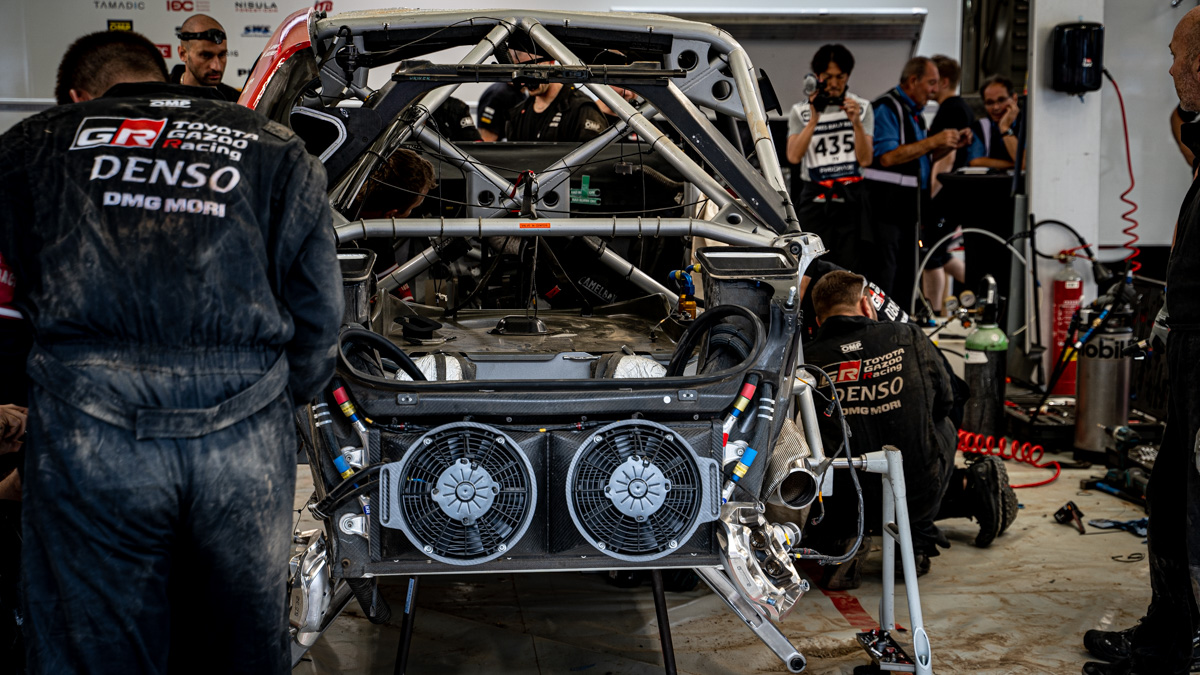

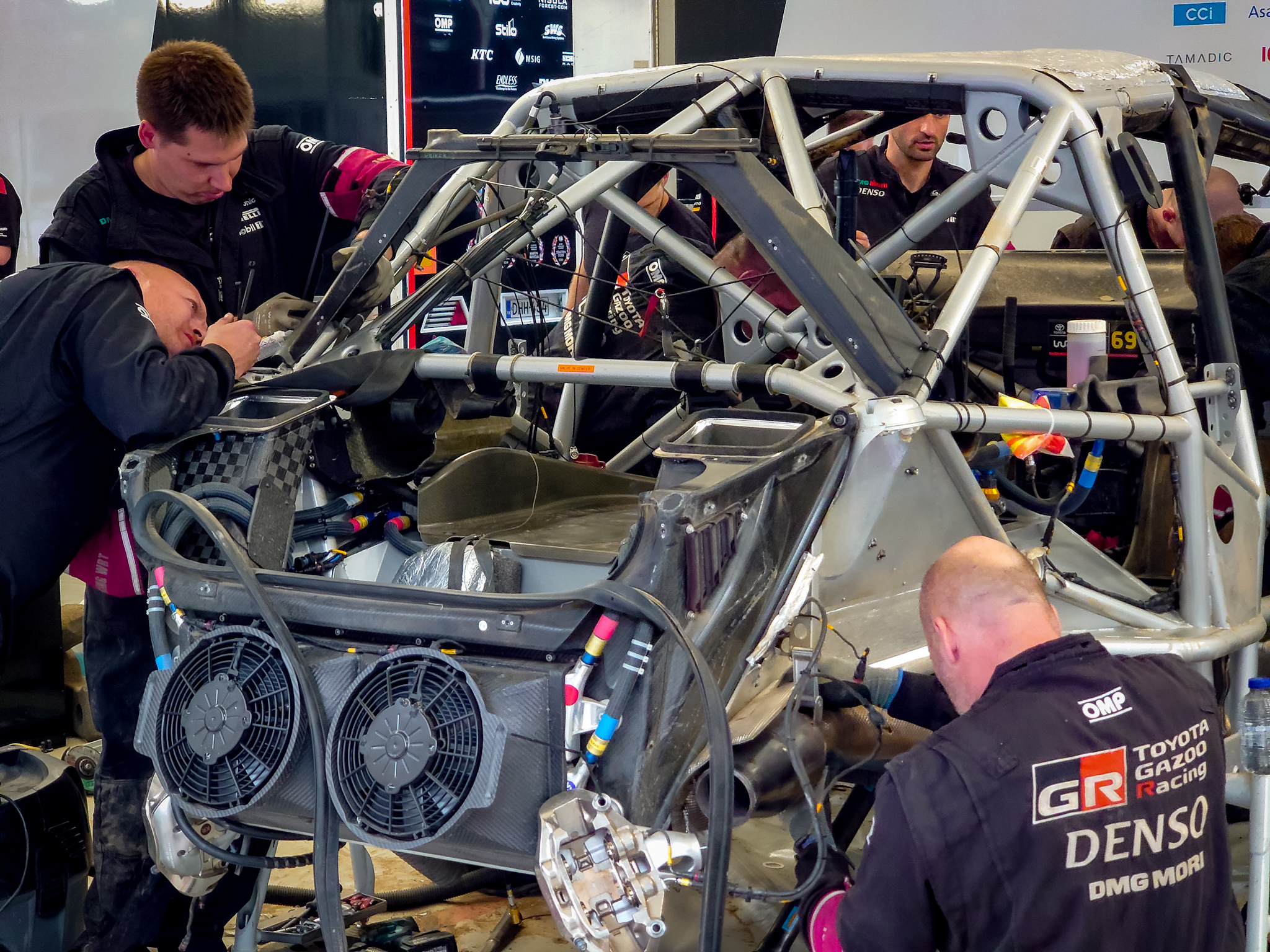

The central chassis space frame is formed around three main hoops encapsulating driver and co-driver, with extensive triangulation between them. The lower door sections sport considerable reinforcement, augmented by large areas filled with energy-absorbent foam of varying densities. Tied in to the central cage are support structures to carry the front and rear suspension assemblies.

Previously, the production chassis structure would extend to the furthest extremities of the cars; however, the new tube frame construction stops just beyond the front and rear axle centerlines, with only bodywork supports reaching past this point. Located in the center of the chassis is the 100kW hybrid system, with the battery, control electronics and traction motor all housed in single protective casing.

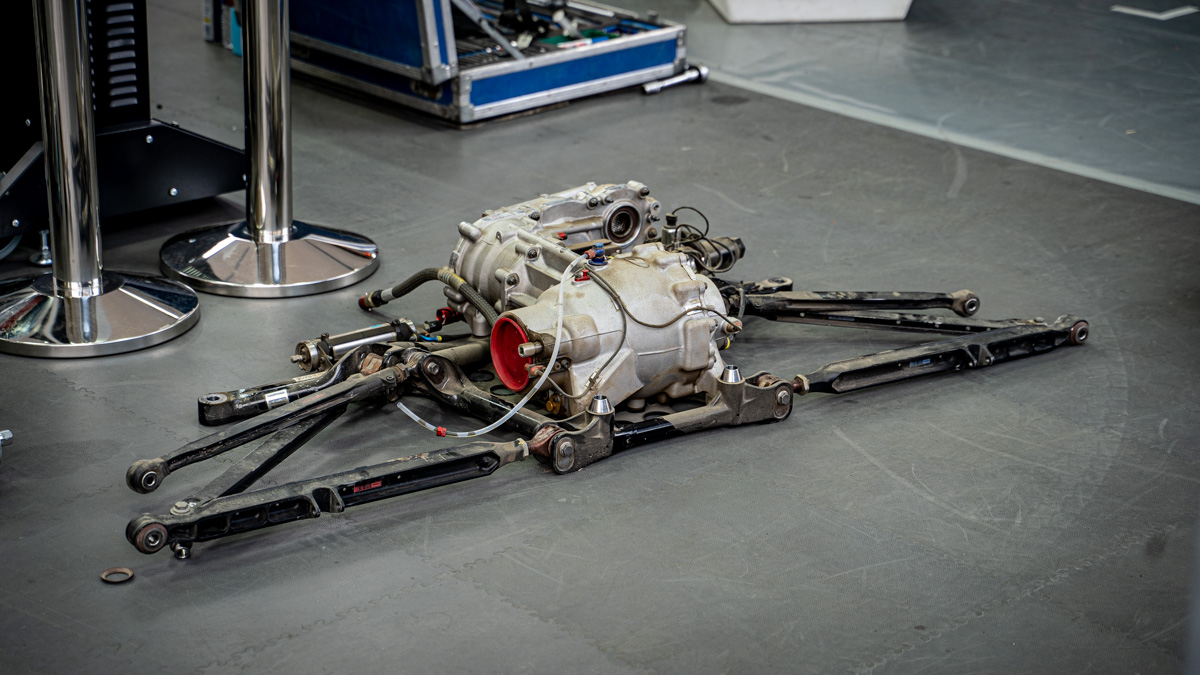

The decision to locate all the HV components within the safety cell, including the motor, has, when coupled with a need to accommodate the four-wheel-drive system, led to an unusual drivetrain layout. The hybrid motor is located off the centerline of the car, to make space for the main propshaft, which runs from the transmission through a cutout in the hybrid housing to the differential. Drive from the electric motor is transferred via a second propshaft that connects to a transfer gearbox, which forms part of the rear differential housing (see A tight squeeze, page 16). Beyond the addition of the hybrid system, the regulations simplified the transmission systems that teams are permitted to run. In place of the six-speed, paddle-operated units with active center differentials – used until last year – the cars now run five-speed units with a standard sequential shift and no active diff.

Design directions

The move toward a semi-spec tube chassis could have restricted design freedom, but Toyota technical director Tom Fowler says, “I think the total amount of freedom is probably about the same; it’s more a shift in freedom.” He highlights the design of the front suspension crossmembers as a case in point. Previously, the rules dictated that certain parts stayed in their stock (production car) locations and had to be worked around. “Depending on your base car, this always gave a certain challenge and ruled out certain concepts for sure,” notes Fowler, adding, “In that sense, the freedom of design is increased.”

However, large portions of the chassis are now tightly prescribed by regulation. “Compared with the previous safety cell, there are more members involved. We have ended up with a fair few geometric constraints in the safety cell and the limitations have increased,” says Fowler. M-Sport technical director Chris Williams adds that there is still some scope for teams to stamp their identity, even in the central portion of the car. “You will see that all the cars appear slightly different where we’ve taken the regulations and adapted the architecture to how we want to best present each of our cars for overall stage performance.”

The layout of the suspension struts, specifically their location in relation to the axle centerlines, is one area where teams diverge in their approaches. Both M-Sport and Toyota have previously offset their suspension struts relative to the axle line, allowing for a longer damper to be fitted, giving greater travel. Conversely, in the previous WRC era, Hyundai mounted its dampers in line with the axle. For 2021, the approaches flipped, M-Sport and Toyota placing them in line, Hyundai going for a (somewhat extreme) offset. Among the downsides of having an offset damper is the increase in friction its angle creates between shaft and body, thanks to the bending moment that is introduced.

When asked about Toyota’s approach, Fowler explains that with travel now limited to 270mm (WRC previously had no limit, with Toyota and M-Sport running more than 300mm), “One of the first questions that our suspension design team was asked to answer during the very early concept stages was, ‘Okay, we’re going to limit the travel to roughly X, can you fit a strut on top of the driveshaft without having to offset it, and still have the maximum travel?’ After some work, the answer was ‘yes’. So that’s where it went.”

Also impacting the design and operation of the new cars are rules governing the interchangeability of parts, referred to by some as the R5 principle (after the tightly cost-controlled second rung of the WRC ladder, now termed Rally2). This means that parts such as uprights must now be interchangeable corner to corner, theoretically reducing teams’ inventory and thus costs. The result is that engineers have less setup flexibility than previously. “We would have very specific parts for tarmac, gravel, left and right sides, with a huge catalog, which helps with adjustability,” says Fowler. “[With interchangeable parts] you have a limitation on how you design the kinematics, and the geometry gets more difficult. What that has done is mean everyone has had to be a bit clever to keep adjustability and make sure there is still some room to play.”

Hybrid drive

The move to hybridization was championed by several current and potential new-entrant manufacturers and, in the words of former Hyundai team principal Andrea Adamo (speaking when the rules were being signed off in early 2020), “Hybridization is definitely needed, because rallying is a marketing tool, full stop. If we want to survive, we need cars that are justifiable from a marketing perspective.” On top of the need to incorporate technology that OEMs could market as road relevant, cost control was a primary concern, hence the move to adopt a spec system from a single supplier across the class. Not all manufacturer teams felt that this was the best way forward. Fowler states that Toyota would much rather have had the freedom to develop its own system, even within tight regulatory constraints. However, he accepts that for the wider benefit of the sport, if a single supplier system was needed to assuage manufacturers’ cost fears, so be it.

Developed and supplied by German company Compact Dynamics (now a subsidiary of Schaeffler), following a tender process conducted by the FIA, the hybrid, which operates at 750V, consists of a single drop-in unit tightly encapsulated within what is effectively a ballistic box containing the motor, its inverter and battery, with the complete unit tipping the scales at 87kg. The units are mounted centrally in the cars’ chassis, behind the driver’s and co-driver’s seats. The only external connections are liquid cooling circuits for the motor; inverter; battery (supplied to Compact Dynamics by Austria-based Kreisel Electric), which uses direct fluid cooling of the individual cells; and the charging system. The cars are capable of fully electric operation, which must be used on certain non-competitive stages of each rally, with a range of 20km possible thanks to the 3.9kWh battery capacity. The battery can support a 40km range; however, in the name of longevity its capacity is underutilized for pure-EV road sections.[pullquote]Hybrid workarounds

The arrival of hybrids has not been trouble free: some problems have made it into the public domain while others have stayed behind the scenes. According to M-Sport’s Chris Williams, early component-based issues were dealt with quickly and by midway through the year: “If something was going to fail, it’s failed.”

However, there remain some persistent bugs in the system software, relating to issues such as failure modes that can stop the hybrid operating based on false alarms. “I think they just missed some of the interactions going on with the units,” adds Williams.

To combat this, teams have been forced into developing workarounds using the control they have over the software. Williams notes that, “There are still ongoing issues that we kind of manage that you’ll never see. Unless it’s a critical bit, we have the ability to reset the system really fast, on an automatic reset. If there is a false call in the system, bang, we can reset it and the driver probably doesn’t even notice.”

Toyota’s Tom Fowler is more vociferous about the issues; Toyota was an early casualty when Elfyn Evans was forced to retire from the second round of the season in Sweden, after the lights showing the hybrid system status failed. The parts in question were not under Toyota’s control, Fowler says.

“When we encounter a problem, we hound the life out of it until we’re sure it’s fixed. And if we don’t fix

it, and it happens again, we’re incredibly pissed off with ourselves. To have a part where we don’t have that ability, we can’t strip it open to see with ourown eyes exactly what happened, is incredibly frustrating. And I think this makes the glitches more difficult to handle.”

Fowler’s frustration at the processes in place to handle problems with the system is tangible, and his team’s only recourse has been to analyze the circumstances around failures in an attempt to identify trends and try to avoid them in the future.[/pullquote]

Characterization

As soon as the first development hybrid units reached teams in 2021, they were keen to characterize them and develop control strategies, as Williams recounts. “The very first thing we did was take the unit and put it on the dyno, to be sure we could control it, make sure that we could calibrate it. After that we’re doing lots of work on the dyno to make sure that we can control it with the strategies we want to do, that will get the best performance.”

Mapping power delivery from the MGU and, just as importantly, energy recovery under braking, was an area of intense development for every team. Under the rules, each manufacturer has been permitted to homologate three deployment and three energy recovery maps, shared across all of their drivers, which are then fixed unless a team chooses to play a ‘joker’ – a rules mechanism that enables a limited number of updates each year. These maps must be balanced to work on both tarmac and gravel stages and suit a variety of different driving styles. The drivers can switch between maps over the course of a rally, but not during a competitive stage. The experience across the grid of handling this element of the hybrid certainly appeared to vary.

Julien Moncet, deputy team director at Hyundai, remarks that in the early days of development, his drivers found it hard to manage and the power delivery left much to be desired. “The system was not predictable, and was disturbing how they were driving,” he says. “This is what we have improved the most. We are not using the system at all in the same way as we used to. We have brought a lot of updates in this area.” He also points out that the banning of fresh-air-based anti-lag systems for the ICE further complicated the task of keeping the cars as driveable as possible.

From Williams’ perspective, M-Sport had its hybrid well understood from the outset. “We put in an enormous amount of effort last year to be up and running early. To try and understand the system, we developed a few tools to be able to train the drivers and also to be able to analyze the feedback and the results quite quickly. By the time we got to Monte Carlo, we were match fit and race ready with hybrid. We haven’t changed philosophy [since then], just a few parameters, probably more in trying to keep the FIA happy than anything else.” For the first year of the new rules, teams were permitted an extra joker specially covering mapping. This means that in addition to a general software update joker, which covers the whole car, they also have access to a hybrid-system-specific software joker to use through the year.

Much like Hyundai, Fowler feels that his team had plenty to learn at the start of the season. “When we had to homologate the three maps back in January, we’d never driven in Sardinia or Ypres, for example. There was a lot of test information missing against the base software; most of the learning we’ve done during the season has been about improving the mapping so that it’s more flexible.” Having already used one joker (as of Ypres in August) Toyota plans to deploy its remaining joker on a revised tarmac-specific map for the final two rounds, both tarmac events, which Fowler says, “brings together all of our tarmac learning from across the season”. He adds somewhat mischievously, “Of course, if it was completely open, I’m pretty sure we would have a different mapping for every single rally of the season, and probably two or three for each rally.”

Aero restraint

2022 saw the freedom afforded to aerodynamicists reined in, following what can only be described as the excesses of the previous regulation set. Fowler remarks, “We enjoyed what happened with aerodynamics in WRC from an engineering point of view but it was a bit silly. Probably a big proportion of the fault lies in our design office. Maybe too much coffee or too many late nights or something! I think the regulation going in this [new] direction was good for everybody.” Complex elements such as dive planes, wheel arch louvers and rear diffusers are now banned, as is the intricate ductwork under the hood, used to fine-tune airflow over the outer bodywork.

Aerodynamics are still important, but the sum performance contribution of bodywork additions is now less potent than before. Fowler does, however, caution that when rules become more restrictive they are also harder to police. “When you don’t have laws, or very few, just simple laws, you can easily monitor what’s going on. But when you have very strict rules, in order to keep the integrity of them you have to police them strongly.” This has changed the relationship between teams and the FIA in terms of ascertaining what is and isn’t allowed. “One of the things with how we deal with aerodynamics with the FIA, which differs from the previous, is that we have been sharing 3D CAD with them for many months. We’d been showing them our planned homologation bodywork and then getting feedback about whether it complies with the rules or not,” said Fowler. On this last point, all three works manufacturers’ initial stabs at bodywork fell foul of what the FIA envisaged and they were told to go back and try again.

[pullquote]Cooling conundrums

One particularly challenging aspect for the teams, related to both the aero package and the hybrid system, was cooling the latter. Looking across the service park, considerable variation in the packaging of elements such as cooling scoops on the rear quarters and their associate internal ducting were to be seen. Toyota’s Tom Fowler notes that initially, his engineering team did not think it would be possible to incorporate sufficient cooling capacity (within the constraints of the rules) to accommodate the hybrid’s needs across all rally conditions. However, after an intense development program in both the virtual and physical domains, he felt they reached around 95% of the capacity required. It is notable that Toyota has consistently sported sizeable ducts at the rear, particularly when compared with Hyundai’s setup (which also appears to be more compact within the shell). M-Sport’s Chris Williams says that the team has managed to keep the hybrid within its thermal limits across the season. Though, “We do occasionally give them a fright,” he quips. He hints that at least in the case of the Puma, the hybrids have been known to automatically derate as a protective measure. However, he notes that this is not a significant issue for overall car performance. “If you are trying to use the full 100kW, and you have 200kJ of energy, that is two seconds of deployment. Even if the system derates to 80kW, you use that energy in 2.4 seconds, at 60kW it’s 3.2 seconds. You still use all the energy so the [performance] difference is not massive.” [/pullquote]

Williams highlights, “I think it’s fair to say, we’re very focused in one area that we know if we can improve, we’re just going to go faster. We’ve lost a chunk of that this year. “We spent an awful lot of time last year developing that area. We then had a sizeable difference of opinion with the FIA in August last year. The result was that all the teams, or at least us and Toyota, had to make some fairly large changes in a short period of time, to align our understanding of aerodynamic features with the FIA’s [interpretation]. We have spent quite a bit of time trying to get back to the numbers that we had developed last year.”

In Fowler’s opinion, despite the aero regulations being more restrictive, the engineering challenge is as hard, if not harder, than before. “It doesn’t change the aero race much, and in some ways, it is more important for your [base concept] to be correct.” Whereas previously, elements such as balance could be addressed with various bolt-on additions, now teams’ aerodynamicists are more reliant on the underlying body shape. “With the current regulations, finding that first chunk of performance is really difficult and is more about how the car is working as a package, ensuring it operates as a cohesive whole.” The rule changes have slowed the cars down, and thanks to the hard line taken by the FIA on surface features, Fowler does not think it is possible to get back to the same level of aero performance seen up until 2021.

Williams concludes, “The FIA have been fairly forceful, let’s say, pushing the aero in the direction that they want. And anything that was even marginally in the gray area has all been removed. So you will see the cars look in certain areas very similar [because of that].” One notable aerodynamic trend in 2022 has been an increasing use of chassis rake to help improve the performance of the now more limited underfloor aerodynamics. Unsurprisingly, Toyota appears to be the leader, with its car exhibiting noticeably more chassis rake than the others at the season opener. Since then, Fowler says, “I think we have started to see a trend of the other manufacturers trying to sort of follow. If you look at the cars now, I’m not sure it’s much different between everyone. It’s one of those things where it’s quite nice if someone tries to do what you’re doing, because by the time they do it, you’ve decided to do something entirely different anyway. “I think we’re seeing that already. We’re also quite happy if people think that more rake is better. Because that might not always be the case!” It is still early days for this generation of Rally1 machines, but it would appear the all-new approach has not noticeably harmed the spectacle, while giving the sport’s drivers and engineers some fresh challenges to contend with. However, discussion is already afoot surrounding the next shift, due in 2025, which will likely see new powertrains and an evolution of the chassis rules. However, there is concern across the service park that any changes will need to be confirmed soon, with teams conscious that 2024 is looming on the horizon: the point at which they will need cars on stage testing.